From the author’s desk

Pete Rose: A Manager Again, in Bridgeport

BRIDGEPORT, Conn. — He is not the manager we remember, if we think of Pete Rose as a manager at all. Back then, mid- to late-1980s, his momentous playing career just finished, his appalling betrayal not yet in evidence, Rose led his hometown Reds for 785 games. He managed each one just the way he had played each of his 3,562 big league games: As if it were the last game he’d ever be part of, as if the season hung in the balance of those nine innings. He managed that way whether he had his two grand on the game or not.

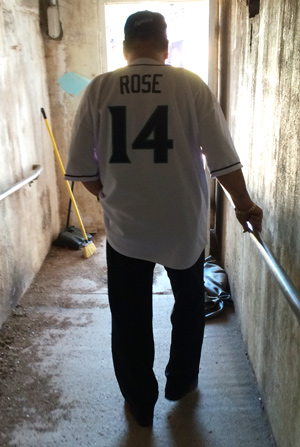

He was full of his Roseian vim then, bluff and gesticulant, carrying on with a kind of amused arrogance, a certainty that he was as good a thing as had ever happened to the game. But now in 2014, a quarter century since he was justly hurled out of baseball for his obstreperous betting, he was far from all of that in time and place, hired to manage the independent league Bluefish in a ballpark hard by a noisy train line in Bridgeport, Conn., a one-day publicity gimmick. Rose is still jocular and frank but humbler, cowed slightly at age 73, limping down the dugout steps on aching knees. He is no longer in it to win it. He managed most of the Bridgeport game from the first base coach’s box so the fans could see him there, a No. 14 jersey on his back but with the same black slacks and black dress shoes he had worn all day.

“Maybe I’ll be remembered as the first guy to manage a professional game wearing Gucci shoes,” Rose said. This was a few hours before the first pitch, and we were sitting in a small conference room in the Bluefish front office. Rose had eaten something from Subway and was feeling relaxed. He took a call on his cell phone from his son Tyler. He put his feet up. “You know,” Rose said, looking back across the years of his banishment, “when I would go back to see a Reds game, everybody working at the park was on edge. Like, ‘Where can this guy go? Can he go on this elevator? Can he go down that hallway?’ They kind of had to be like that. But it’s nice it’s not that way here.”

A young man on the Bluefish staff came into the room with the official game uniform on a hanger: shirt, pants, belt, socks. That’s when Rose said he only wanted the top. “I’ll wait until I make it back to the big leagues to put on a full uniform,” he said.

He knows of course that this is only a stunt, not a step toward the big leagues. Not really anyway. This is something else. “What it is, is an appearance,” Rose said, “An appearance that in this case has me out on the field managing a few guys during the game.”

Pete got a nice wage for the day—he would not have come if he hadn’t—and the Bluefish surely did too. The team might draw 600 fans on a typical Monday night. This time there were 4,573, at $14 a seat. They also got 200 people to a $150-a-plate luncheon earlier in the day, and 50 more to a $250 meet-and-greet in a ballpark suite before the game. At both events, you could buy autographed jerseys ($300) and autographed bats ($150) and autographed balls and caps and T-shirts. Rose makes good money being the banished Hit King and people make good money off of him, and this was another day in that life.

Still, when Ken Shepard, the Bluefish general manager who put this event together, spoke at the luncheon and again when he addressed the crowd before first pitch, he did not talk about money at all. Shepard is a bright, creative man who was married at home plate in 1994. He is now battling a personal illness with a public bravery that would make you gulp, and what he talked about instead was that this game was making history, baseball history, which, in a certain sense it was.

“Well I guess maybe it is true,” Rose said after pulling on that Bridgeport jersey. “I’m a manager again.”

* * *

The Bluefish and Rose’s people, in particular a Pete handler named Mike Maguire, had been working on this event for months, and the team would never have gone through with it if Major League Baseball hadn’t given the okay. There have been occasional thaws in the ice wall between MLB and Rose in recent years: In 2010 he was allowed on the field in Cincinnati to celebrate the 25th anniversary of his record setting 4,192nd hit. He was allowed on the field again last year for an event uniting the members of the Big Red Machine. Rose has been on the permanently ineligible list since 1989 but maybe, Shepard and Maguire thought, this Bridgeport thing could work.

So, in early April, Maguire contacted the Office of the Commissioner and made the ask. A few days later Maguire got a letter, dated April 14, 2014, Rose’s 73rd birthday. It read:

Dear Mr. Maguire: At your request, this letter confirms that if Pete Rose were to manage the independent league Bridgeport Bluefish, this office would not consider such activity to be a violation of the August 23, 1989 agreement between this office and Mr. Rose. Sincerely yours. Thomas J. Ostertag. (Mr. Ostertag is a Senior Vice President and the General Counsel for the league.)

Photo: Kostya Kennedy for SI

It was a very happy development for Rose (“A birthday present!” he said on Monday) and he seized on it with his customary verve. At the luncheon, he was entertaining and crass and unfiltered. He got up and told a story about playing the horses as a kid with Dud Zimmer, Don’s dad, and he talked about the reluctance of today’s hitters to adjust their approach when down in the count. He zinged the Cubs for all their losing, and he went into detail about his fight with Bud Harrelson in ’73 and also the great Game 6 of the ’75 World Series against the Red Sox. He spoke highly of the just passed Tony Gwynn and of Derek Jeter, and then he told crude bathroom stories about Willie Mays and Joe DiMaggio and another about a farting catcher. When someone’s phone went off Rose said, “Better answer it. It might be Bud Selig.”

These are stories and gags Rose has used before and will use again, but most of the lunchers were hearing them for the first time, and Rose went on for well over an hour in such a lively manner, so that people kept having to put down their iced teas because they were laughing too hard.

(At a press conference later, when someone, strangely, asked if Rose had any advice for Clippers owner Donald Sterling, being as Sterling is also facing a lifetime ban. Rose was briefly at a loss for words. Then he said, “The only thing I can say about Donald Sterling is that my fiancee is a lot better looking than his girlfriend,” which just went to remind everybody once again that Pete will always be Pete.)

And then there was baseball, independent league or not, and Rose was in the game. He watched batting practice from behind the cage beside Butch Hobson, the old Red Sox third baseman who now manages the Lancaster Barnstormers, the Bluefish’s opposition. When a Bridgeport outfielder, former major leaguer Joe Mather, hit four straight balls to medium centerfield, Rose, who in his day meticulously sprayed line drives around the field during BP, chided him for wasting his time. “What are you doing, practicing the sacrifice fly?” Mather heard that and cut down on his swing and soon began stinging the ball. Later, in the second inning, Mather slapped a routine single into right-centerfield, then rounded the bag hard, right past Rose at first base, and hustled safely into second with a headfirst slide. Mather was born on July 23, 1982 in the town of Sandpoint, Idaho, and he knows exactly who Pete Rose is.

“It definitely crossed my mind that he was there. I wanted two bases all the way,” Mather said. He had three hits in the game and said that Rose’s rebuke about treating batting practice as if it mattered, as if it were the game itself, was a lesson learned. “That will now stay with me the rest of my career,” Mather said.

Rose enjoyed himself, he said, and he liked that there were a smattering of ex-big leaguers on the team. He admired that they were still here, where salaries cap at $3,000 a month, for the chance to play baseball, and maybe one more shot at the bigs. In the dugout, players talked about guys who’d gone from this independent league to the Show, like pitcher Jerome Williams and Bridgeport outfielder Wily Mo Pena, who used to hit home runs out of Harbor Yard Park and onto the roof of Webster Bank Arena beyond leftfield.

Pete Rose won’t manage in the Major Leagues or in any affiliated minor league ever again. And there is no telling whether Bud Selig or the commissioner who succeeds him will soften on Rose’s ban. But on this night, even through the sideshow stunt of it all, there was a pro baseball game in Bridgeport, bases 90 feet apart. Rose came out and met the umps at home plate and he clapped and yelped instructions from the first-base line, and he talked about hitting with a couple of the guys. His fee was paid and it was a good night (the Bluefish won 2-0) and, said Rose, “it is always good to be around baseball players.”